“The first brushstroke applied in an artwork is a kind of ambiguity that forms as things meet and collide on the fringes of the artist’s thoughts and meditations, and the concrete form of that ambiguity is abstraction. Within the scope of metaphysics, my paintings may be a kind of ‘painted’ philosophy.” (Sen Chung, “Excerpt from ‘Romanticism of the Stroke,’” Art in Culture, 2021)

The world of the painter starts in a small rectangular frame. The space in that frame expands infinitely as it attempts to reach the ends of eternity. There is an unfathomable depth that can be glimpsed in an empty canvas. Yet in that place offering the potential to begin something or another, the painter ends up frustrated by the fact that their questions and beliefs about the essence of their object can never be fully captured in language and form. The materials of representation—the paints—manifest this whole process on the canvas as a pictorial event. Within the marks left behind, we come face-to-face with the artist’s presence. Recorded there are a series of decisions extracted from the limited dimension of life, the movements of the body and the trajectories of thoughts. In this way, the material medium of painting is laden with layers of information that are not readily reducible to language. The painting’s creation is bolstered by the sensual collisions and harmonies of the canvas’s individual elements, giving evidence of the moments spent by the painter. In those moments, we can examine the absolute conditions of life that we are assigned as human beings: the contemplations of living and dying, the senses of suffering and play, and even the relationship between a single, minor individual and the vastness of the world.

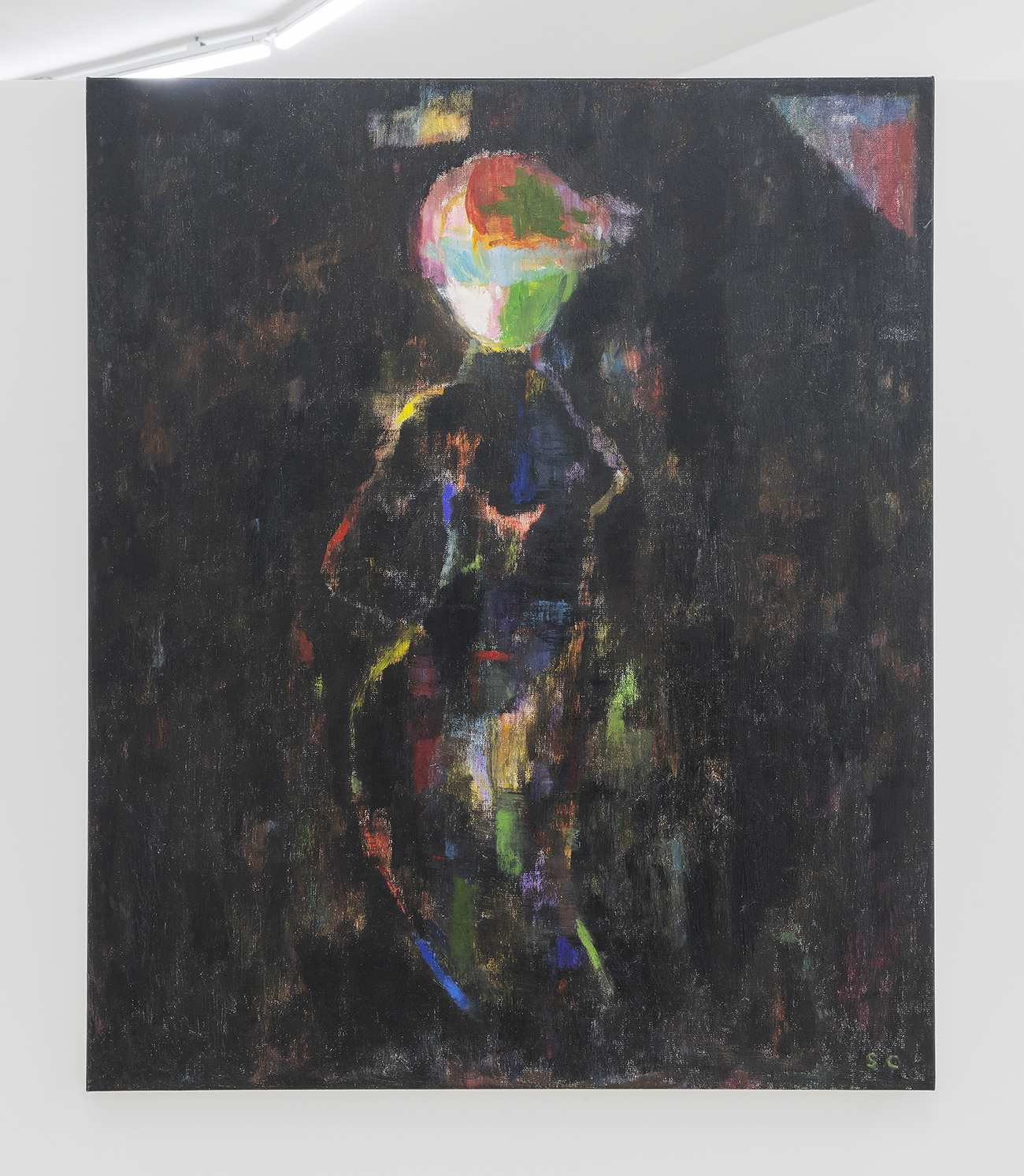

Sen Chung situates his canvas between himself and a realm of invisible ideas. He uses his small rectangular spaces to discuss the cosmos, and by exploring the cosmic order, ephemeral beauty, and the sublime, he necessarily ventures into a world of abstraction. Using figurative references from the past, he seeks to capture the beautiful and sublime, as well as the tension between finite human being and an absolute cosmos. The passive, lyrical qualities grounded in his unique meditative gaze are often visualized through women and shapes drawn from nature. But owing to the rigidity or limitations of the form’s linguistic boundaries, he has gradually come to pursue the forms of abstract painting. The representational motifs that frequently appeared in his early work—people, animals, natural landscapes, and architectural styles among them—fell increasingly by the wayside. With his most recent work, he primarily uses geometric figures and restrained colors. Metaphysical objects tend to become more divorced from their essence as their references become more concrete. An explicit linguistic approach merely engenders endless slipping. Because of this distant quality, this inability to achieve the capturing of an object on an empty canvas, the work ends up as a neutral canvas where nothing more can be added or removed. The resulting minimal lines and geometric shapes are depicted in restrained, delicate fashion. Not reliant on concrete shapes, the canvases depict the cosmic structure and order through the dynamic energy that are achieved as the weight and density of contemplation are stripped away.

Rather than shaping meaning through combinations with externally existing objects or contexts, Chung’s work consists of points, lines, and planes as basic aesthetic elements. They are akin to a “cosmos” constructed through a delicate tightrope walk between tension and equilibrium. It touches on that realm of absoluteness that traditional abstract painting has sought to achieve. Utter abstraction, where all traces of the referent have disappeared, represents a desire for perfect moments, as well as a consummate state that we fear might end up ruptured. At the same time, we should also examine the parts where no paint has been applied in these cosmos-paintings, constructed with inscrutable principles and abstraction that can never fully be subsumed into language. Those empty spaces are like pathways opened up toward the totality beyond forms and linguistic systems, which cannot be captured through material elements such as paints. In the process, the artist established “infinite vistas” on his canvas, possessing an ineffable sense of space and atmosphere. Meanwhile, the emotions that permeate his works—exemplified by longing, distance, nostalgia, and melancholy—afford his work a sense of immersion that transcends space and time.

In Chung’s paintings, Eastern ink-and-wash painting overlaps with Western romanticism. Indeed, the artist has commented that “romanticism is the Western artistic trend that I see as most closely neighboring the spirit of Eastern painting, with its emphasis on the essence and spirituality of things.” This is true in the methods of composing the canvas: the transparent expressive style with layers that recall the glistening of Eastern painting, the monochrome backgrounds, and the arrangement of the canvas’s geometric shapes and colors as allegorical reinterpretations of romanticism. This creates an intermediate ground where images can be observed through the layers formed by the intersection, blending, and overlapping of color and shape. In other words, shapes fixed in place by the external use of pictorial materials represent a way of establishing a layered canvas that encourages profound meditation through a reflection of the interior world based on the inherent qualities of painting: its two-dimensionality, composition, colors, and materiality. There is also something very Eastern about the artist’s unique perspective, his meditative stance of favoring internal reflection, rapport, and acceptance over actively responding to and intervening in nature and the environments that surround human beings. This shares parallels with the romantic perspective centered on human emotions, personal experience, and feelings of respect and awe toward nature. Grounded in this point of view, the artist’s work attempts to establish a close connection between human existence and the natural world, while recognizing the importance of the individual’s inner life and emotions. Distinctive canvases are formed as the Eastern approach to contemplation, with its pursuit of inner peace and reflection, overlaps with the emotional depth and free expression of individuality sought in Western romanticism. In the process, the viewer is urged to achieve a deep understanding of fundamental questions about human existence and the universe.

This exhibition presents work from a period beginning in the mid to late ’00s and continuing until recently. Sen Chung has adhered to a consistent approach of using the inherent, particular qualities of painting to question the fundamental internal principles within and beyond phenomena. Taking a step back from the sorts of “shocks” that have been repeatedly emphasized in the contemporary context, his abstraction is somewhat free from the era’s philosophical backdrop and narrative demands. In a sense, it may also connect with human nature. This stems perhaps from a desire to meet aesthetic demands and explore the essence of art through the oldest of media. Viewing San Chung as a painter who approaches his canvases in a constant attempt to reach the unapproachable, we see his attitude toward an inviolable realm of contemplation, a world of formidable transcendence. There is a romantic drama at play here: an attempt to detect the world in the realms of individual emotion, freedom, creativity, and imagination—to confront it in a more intuitive and self-directed way and understand it at a philosophical level. The fundamental explorations of the beautiful, sublime, momentary, and eternal spin and spin before converging on the question of “what is painting?” This is the mission incumbent on the artist in his attempt to understand the world through the methodologies of painting. Since this is an act of roaming in search of unattainable origins, it means confronting an eternally incomplete world, and so the painter must constantly pose questions about painting. Chung has said, “The world makes me think of painting, and painting opens that world up like destiny.” This belief shows his approach to the canvas as a painter—and it may represent the reason for the strokes he applies to that empty space.

Credit

Participating artists : Sen Chung

Curated by KIM Sung Woo

Text by KIM Sung Woo

Design by YO Daham

Installation technician : Mujindongsa

Photo by CJY ART STUDIO (CHO Junyong)

Supported by Arts Council Korea, 2024 ARKO Selection Visual Art